F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel turns 100 this year. What does its hero tell us about how we see ourselves?

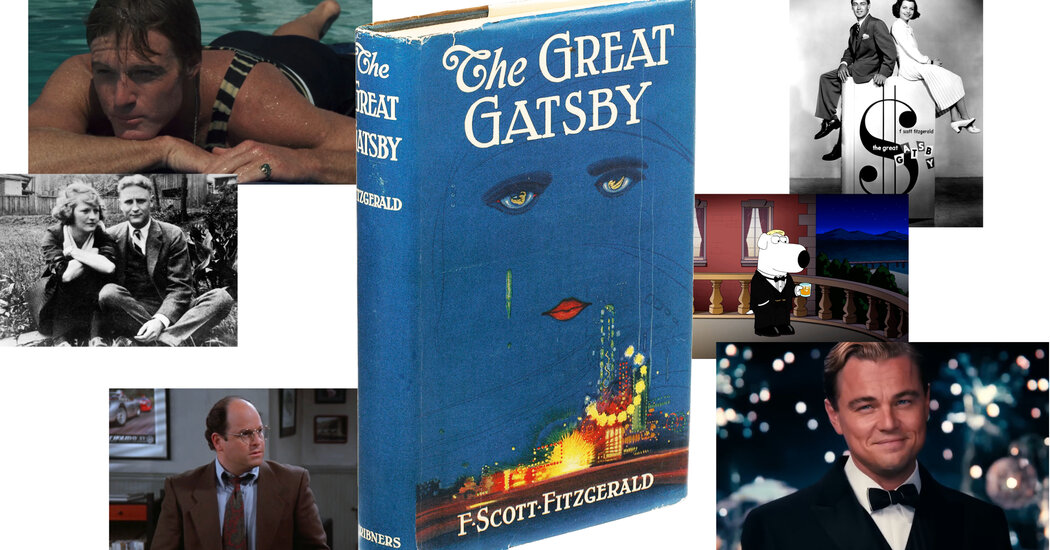

A collage of pictures and movies together with the actors Robert Redford and Leonard DiCaprio as Gatsby, scenes from “Seinfeld” and “Household Man,” and a picture of the primary version of the guide.

And so we beat on, boats against the current, borne ceaselessly back into a book that its author considered calling “Trimalchio in West Egg.” Would we still be talking about it if he had?

But he called it “The Great Gatsby” and we are.

A century after its publication, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s slender novel about a mysterious, lovelorn millionaire living and dying in a Long Island mansion is among the most widely read American fictions.

Published when Fitzgerald was just 28, following two exceedingly popular novels and two collections of stories, “Gatsby” chronicles its title character through the eyes of his neighbor, Nick Carraway, a Yale grad with a philosophical streak. Jay Gatsby, whose real name is James Gatz, is in love with Daisy Buchanan. Daisy’s husband, Tom, is a blowhard, a bigot and a philanderer — a paragon of old money gone bad. These rich, careless people wreck everything around them. Gatsby winds up dead, shot by the wrong jealous husband, and Nick is left to ruminate on the meaning of his friend’s sad, perplexing and somehow quintessentially American life.

A collage of pictures and movies displaying appearances of “The Nice Gatsby” in widespread tradition. On the middle: a 1974 version of the novel that includes Mia Farrow and Robert Redford on the duvet.

The green light in Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby” (2013)

A Metropolitan Opera production (1999)

Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan (1974)

The Gilded Age mansion that may have been a model for Gatsby’s own

A “Great Gatsby” party at a New York nightclub (2015)

A movie tie-in edition (1974)

Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda

The green light in Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby” (2013)

The Gilded Age mansion that may have been a model for Gatsby’s own

Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda

A Metropolitan Opera production (1999)

A “Great Gatsby” party at a New York nightclub (2015)

Mia Farrow as Daisy Buchanan (1974)

A movie tie-in edition (1974)

The ruminating hasn’t stopped, and neither has the recycling of Gatsby’s tale. High school students churn out papers on the American dream, the Lost Generation and the symbolism of that green light at the end of the dock. Playwrights, filmmakers, cartoonists, rappers and not a few novelists have taken their shots at turning Fitzgerald’s text into something new, all while paying tribute to its unparalleled staying power. It’s been grist for at least four feature films, countless television episodes, an opera, two musicals and — especially since it entered the public domain four years ago — a smattering of fan-fiction sequels, prequels and retellings.

What we think about Gatsby illuminates what we think about money, race, romance and history. How we imagine him has a lot to do with how we see ourselves.

Here is a brief, roughly chronological guide to some of the more striking and improbable Gatsbys of the past century.

Jazz Age Gatsby

When he published “The Great Gatsby,” Fitzgerald was more than just a famous writer; he was a celebrated generational voice, the Sally Rooney of his time. His previous novels, “This Side of Paradise” and “The Beautiful and Damned,” helped establish the mythology of a self-mythologizing era. Fitzgerald’s 1922 story collection, “Tales of the Jazz Age,” had branded the zeitgeist, certifying the young author as one of its creative directors.

The language of advertising is apt. Part of what made the Roaring ’20s roar was a newly vibrant commercial culture, an aesthetic of consumerism, leisure and mass entertainment promoted by glossy magazines, Hollywood spectacles and Broadway shows.

Fairly or not, “The Great Gatsby” was folded into a world of Prohibition-fueled naughtiness, Wall Street-enabled materialism and the anomie that followed the Great War and the great influenza pandemic. Flappers and roadsters, dance crazes and speakeasies, decadence and daring: All of that clung to the book like smoke curling from a lacquered cigarette holder.

A collage of pictures and movies relating “The Nice Gatsby” to the aesthetic of the Jazz Age. Quick clips from movies like “Some Like It Scorching” and “Chicago” accompany a shiny inexperienced version of the novel that was carried by troopers in World Struggle II.

A scene from Luhrmann’s film (2013)

Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse in “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952)

Marilyn Monroe in “Some Like it Hot” (1959)

The Fitzgeralds with their daughter, Frances (1925)

A U.S. Armed Services edition from World War II

A first edition of “The Beautiful and Damned” (1922)

Renée Zellweger in “Chicago” (2002)

Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse in “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952)

A first edition of “The Beautiful and Damned” (1922)

A U.S. Armed Services edition from World War II

Marilyn Monroe in “Some Like it Hot” (1959)

A scene from Luhrmann’s film (2013)

Renée Zellweger in “Chicago” (2002)

The Fitzgeralds with their daughter, Frances (1925)

But “Gatsby” was, at first, less successful than its predecessors. Reviewers shrugged. Sales were sluggish. The novel and its author slid toward obscurity. The ’20s ended with the stock market crash, and tales of wealth and abandon didn’t age well in the Depression. Prohibition was repealed, and Fitzgerald’s style and subject matter fell out of vogue. For a while, nobody wanted to hear about Gatsby or his era.

The posthumous revival of Fitzgerald’s reputation (he died in 1940) was partly the work of literary critics, among them his friends Malcolm Cowley and Edmund Wilson, and partly the work of the U.S. military, which distributed more than 150,000 copies of “Gatsby” to American servicemen during World War II.

Postwar American popular culture was a nostalgia machine, and the ’20s, an era of optimism and abandon before the more recent hard times, provided ideal raw material. Gatsby and his age were never out of style for long. His story was retold periodically on television and in the movies, and the character became an archetype. Meanwhile, knee pants and newsboy caps, flapper dresses and cloche hats, Deco and dissipation flickered across the screens (in “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Some Like It Hot,” in “Funny Girl” and “Chicago”) and the fashion pages. Every bull market brought back giddy, anxious memories of the good old days. Which came to be called the “Great Gatsby era.”

Existential Gatsby

After World War II, as readership of “The Great Gatsby” grew, its cultural footprint expanded. Paperback editions proliferated, and the novel was name-checked by younger authors, including J.D. Salinger. Hollywood, which had first brought the book to the screen in 1926, made more adaptations — one in 1949 starring Alan Ladd, and one in 1974 with Robert Redford as a notably melancholy version of the mysterious millionaire.

The book came to be seen less as a satire of the ’20s than as a commentary on the predicament of modern man — a precursor to popular contemporary novels like Albert Camus’s “The Stranger,” Saul Bellow’s “Dangling Man” and Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye.” Gatsby’s life is marked by alienation and longing. His death, an act of senseless violence, is a textbook case of the absurd.

A collage of pictures and movies encompass a picture of the long-lasting first version of the guide, with a shiny blue cowl and a pair of huge luminous female eyes.

Peanuts comic strips from the 1990s

Gatsby on an episode of “Robert Montgomery Presents” (1955)

Snoopy’s Gatsby, a pop-culture philosopher for an age of uncertainty

Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby (1974)

Salinger’s novel gave Gatsby an existential spin.

Alan Ladd stars in “The Great Gatsby” (1949)

Alan Ladd stars in “The Great Gatsby” (1949)

Robert Redford as Jay Gatsby (1974)

Snoopy’s Gatsby, a pop-culture philosopher for an age of uncertainty

Peanuts comic strips from the 1990s

Salinger’s novel gave Gatsby an existential spin.

Gatsby on an episode of “Robert Montgomery Presents” (1955)

Enter Snoopy, the quintessential existential Gatsby. Snoopy’s bow tie-clad, world-weary alter ego appeared in 1998, part of a series of Gatsby-themed Peanuts strips. Snoopy’s version of the character emphasizes not the hurly-burly of the Jazz Age but the malaise and anxiety that defined Gatsby in the second half of the 20th century.

Snoopy projects an aloof romanticism that was a major part of Fitzgerald’s legacy. He plays the novelist’s hero like the protagonist of a European art film.

A singularly literary, exquisitely sensitive cartoon animal — a would-be novelist in his own right, pounding away at the typewriter on the roof of his doghouse through dark and stormy nights of the soul — Snoopy dwells in a world that is all action and no plot, a novel without beginning or end. Like Gatsby, he’s self-invented. (One of his imaginary selves fights in World War I, just like Jimmy Gatz.) And, like Gatsby, he’s a pop-culture philosopher for an age of uncertainty.

High-Low Gatsby

In 1945, New Directions published an edition of “The Great Gatsby” with an introduction by Lionel Trilling, a critic and Columbia professor on his way to becoming perhaps the supreme American literary intellectual of his day. Trilling’s essay installed Fitzgerald in some formidable company. Referencing Milton, Goethe, Yeats and “The Brothers Karamazov,” Trilling made the case for “Gatsby”’s greatness.

While Trilling and other academic power brokers succeeded in placing “Gatsby” on the highest shelf of modern literature, they also turned the novel into homework. Reading can be fun, but in a democratic culture the argument from authority — the idea that we’re supposed to read certain books because they’re important — often backfires, branding the books in question as boring, and their admirers as bureaucrats and snobs.

A collage of pictures and movies surrounding a 1945 version of the novel. The guide has a golden yellow cowl, dominated by a big greenback signal.

The comedian Andy Kaufman reads “The Great Gatsby” aloud.

“Gatz,” performed in New York City (2010)

The literary critic Lionel Trilling made the case for “Gatsby”’s greatness.

“Gatz,” performed in New York City (2010)

The comedian Andy Kaufman reads “The Great Gatsby” aloud.

The literary critic Lionel Trilling made the case for “Gatsby”’s greatness.

In the late ’70s, the comedian Andy Kaufman used to troll his fans (including on an episode of “Saturday Night Live”) by coming onstage in a bow tie and tux and reading “The Great Gatsby” aloud. The joke — the threat — was that he was going to subject the audience to the whole book. Nobody knew whether to laugh or jeer, or whether Kaufman’s disgust was part of the act.

The idea of being subjected to the novel in its entirety was reprised in a 2000 episode of “South Park,” in which a doctor reads the book to a fourth grader and then quizzes him on it as a way of testing for A.D.D.

Why single out “Gatsby”? Because it’s well enough known to signify wealth, by virtue of its subject matter, and obligation, because of its association with school. The episode of “Family Guy” that features Brian, the world-weary Griffith family dog, as Gatsby is called “High School English.”

On “Seinfeld,” when the notoriously unbookish George Costanza dreams of a life of high-toned leisure, he rhapsodizes about being “like the Gatsbys.” (The name also comes up when the J. Peterman clothing catalog, where Elaine Benes works, markets a repurposed brassiere as “the Gatsby swing top.”)

What if Kaufman had kept going? The audience might have been watching “Gatz,” the full-length stage adaptation of the novel that made its debut in 2004 and has been revived several times since, including last November. Produced by a New York-based theater company, “Gatz” takes place in a drab modern office and also, somehow, amid the mansions of West Egg. Not quite a performance and not quite a staged reading — the actors play office workers who recite the text, sometimes seeming to impersonate Fitzgerald’s characters — it belongs both to the rarefied world of experimental theater and to everyday American life.

The show invites you to imagine that “The Great Gatsby” is everywhere. Or to understand that, wherever you are — at work, at school, at home in front of the television — “Gatsby” will find you.

Hip-Hop Gatsby

Twenty-first-century Gatsby iconography is dominated by Leonardo DiCaprio, the star of Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 adaptation, who has been memed across the internet, wielding a coupe of bubbly and a wolfish smile.

The key to that Gatsby, though, is the music. The soundtrack is a collage of contemporary pop and rap — from Lana Del Rey, Florence and the Machine, Beyoncé and others — executive-produced by Jay-Z. The parallels are almost too obvious. Like the jazz of the 1920s, hip-hop is a Black American musical idiom that has become the soundtrack of the era, a complex, fast-evolving art form freighted with aesthetic possibility. Like Jay Gatsby, Jay-Z (also known as Shawn Carter) is a self-made man, a one-time dealer in illegal substances who has ascended to the highest levels of wealth and power.

A collage of pictures and movies centered round a brief clip of Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby in Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 movie.

A scene from “The Great Gatsby” (2013)

Beyoncé helped give Luhrmann’s soundtrack its pop hip-hop vibe.

The Gatsbyesque music-industry melodrama “Empire” (2015)

“G” imagined Gatsby as a hip-hop mogul (2002).

The rapper Rod Wave’s video for “Great Gatsby” (2023)

Jay-Z at the world premiere of Luhrmann’s film (2013)

“The Great Phatsby” episode of “The Simpsons” (2017)

Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby (2013)

Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby (2013)

A scene from “The Great Gatsby” (2013)

The rapper Rod Wave’s video for “Great Gatsby” (2023)

“The Great Phatsby” episode of “The Simpsons” (2017)

“G” imagined Gatsby as a hip-hop mogul (2002).

Beyoncé helped give Luhrmann’s soundtrack its pop hip-hop vibe.

The Gatsbyesque music-industry melodrama “Empire” (2015)

Jay-Z at the world premiere of Luhrmann’s film (2013)

Did Gatsby foretell hip-hop, or did hip-hop invent Gatsby? By now the mythologies are so entwined that it’s hard to tell. “G,” a 2002 film starring Richard T. Jones, Chenoa Maxwell and Blair Underwood, sets the novel amid the rap new money of the Hamptons. “I threw the party of the century/And people came over, no one left sober/And it was all for you,” sings Rod Wave on a brooding 2023 track called “Great Gatsby.” “The Great Phatsby,” a two-part episode of “The Simpsons” from 2017, with guest voices by Taraji P. Henson, RZA, Snoop Dogg and Common, underscores the connection. The plot may diverge from the original, but the premise — blending Fox’s longest-running comedy with its Gatsbyesque music-industry melodrama “Empire” — is rock solid. Jay G, the protagonist, is a hip-hop mogul. What else could a modern Gatsby be?

Which raises the question of who he has been all along. The theory that Gatsby was “a Black man in whiteface” (to cite the subtitle title of a 2017 book) has been in circulation for some time, linking academic scholarship and internet fan theorizing. Gatsby’s outsider status is suggestive, as is the fact that his nemesis, Tom Buchanan, is an outspoken racist, obsessed with miscegenation and in thrall to the racial pseudoscience of the day.

In a brilliant 2023 essay in The Atlantic, Alonzo Vereen describes teaching “Gatsby” to high school students in a way that highlights the indeterminate, “unraced” aspects of the character’s identity. “Gatsby’s American identity is so ambiguous,” Vereen writes, “that the students could layer on top of it any ethnic or racial identity they brought to the novel. When they did, the text was freshly lit.”

The light at the end of the dock is an entire constellation.